BonniBlog

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

|

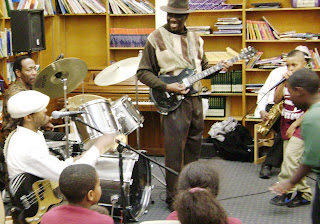

| C.C. Copeland bass, West Side Wes drums, Killer Ray Allison guitar, and Abb Locke (hidden) on sax let the good times roll with kids after school in Donoghue Elementary, on the South Side of Chicago. |

Thought I'd reprint an old column that appeared in Pioneer Press Skyline weeklyfor the neighborhood of downtown Chicago in April 2005. It's just as relevant today. Blues needs to be passed to the next generation! It gives kids another way to express themselves, plus they learn about history and culture. Check out a video about our Chicago School of Blues band which has been giving programs for the charity Rock for Kids.

West Side is the Best Side…

Blues for Kids: Forever, Today

By “Barrelhouse Bonni” McKeown

“The blues are always going to be around, even after all the other stuff dies down,” Chicago blues guitarist Lonnie Brooks told Paul Barile in February 2005, for an article in the Pioneer Press Skyline, a neighborhood newspaper for downtown Chicago

In the same article, several blues industry people bemoaned the state of commercial blues today. Bob Koester, proprietor of Jazz Record Mart and Delmark Records, implied that many of Chicago’s blues men and women remain unrecognized and unrewarded. “A star syndrome has set in,” he said. “Some of the stars don’t move me as much as some of the (lesser-known) artists we record.”

To make matters worse, both Koester and Alligator spokesman Lipkin said they have had to cut back on recording these deserving, lesser known musicians. They note that the entire recording industry is suffering from illegal computer downloading of tunes as well as competition from DVDs. Since blues is a “niche” type of music (like jazz, folk, reggae, and bluegrass) rather than a mainstream kind of popular music like r&b/hiphop, rock, or country, it doesn’t get much airplay on the radio. Corporate, standardized programming does not allow much leeway for mainstream DJs to play blues, so it’s confined to a few shows led by loyal, usually volunteer DJs.

Also, Lipkin pointed out that the core blues audience is aging. There are the African-Americans in their 50s, 60s, and 70s who grooved on it in their youth; white folks who caught up with blues during the folk craze of the 60s or the blues-rock era of the late 80s-90s; and sharp listeners from all ethnic groups who’ve clued into blues as the pure, soulful, down-home root of much of America’s popular music.

One place that the blues finds a new audience is among youth, when guest teachers bring it to them in school or after-school programs. Kids love the boogie-woogie bass lines, repetitive rhythms, and the chance to express their ideas and problems in a catchy, sometimes humorous way.

Teaching music after school blues in 2004 at the Austin Town Hall city park on Chicago ’s West Side, I found that African-American kids in Chicago

Because it’s simple, blues offers students a ready introduction to basic notes, chords and rhythms. With today’s cutbacks in arts education funding, blues might well be the most effective, enjoyable and efficient way to teach basic music skills. Blues is also a great way to teach African-American history, American music history, and creative verse and song writing. And it works very well, as you might imagine, as an outlet for the feelings of youth with troubles and disabilities.

To some extent, blues is already happening in our schools. Each year at the Chicago Blues Festival shows off a class as an example. Fruteland Jackson (yep, that’s really his name and he wrote a song about it!) has taken his acoustic guitar and comprehensive blues workshops to schools and festivals all over the world. Southside teacher, playwright, harmonica and guitar player Fernando Jones has written his own blues education teacher textbook called I was There When the Blues was Red Hot. Harmonica player Billy Branch, guitarist Eric Noden, and singers Shirley King and Katharine Davis, among others, have taken the blues into some area schools. Several of these blues teachers were featured on a 2001 cover of Big City Blues.

But this is a drop in the bucket. Chicago Chicago school of Hard Knox

Could the city sponsor a program which enlists our excellent blues educators to continually train more music teachers, guest workshop leaders, and musicians to give blues programs and lessons in the schools? This would accomplish at least three things:

1) Give kids a simple way to learn music and at the same time connect deeply with Chicago

2) Create a whole generation of new blues fans and future musicians;

3) Spread farther the talent and knowledge of blues educators and musicians;

4) Give more work to deserving musicians, especially the African-American blues men and women who can serve as role models in their communities.

Money for the program might be compiled from nonprofit organizations including existing education programs, arts councils, music businesses and corporate foundations. When there’s a will, there’s a way. And this would be one way to insure that, to pararphrase West Sider Otis Rush, “love for the Blues will never die.”